We were romantics, young Danes who saw early 20th Century New Orleans and its amazing musicians and singers almost in the same light as we had just a few years before seen Ali Baba, Tarzan, that flute-playing guy from Hamelin, and H.C. Andersen's steadfast tin soldier. We didn't grow up with Batman, Superman, or Mary Marvel—our childhood heroes were much older. But then we grew a little and for some odd reason, quenched our thirst for heroes by turning to legendary jazz players and their music. It was real, but still sufficiently distant from our world to trigger the imagination: An old, toothless man of color, rescued from a rice field and led into the spotlight to play a donated horn through donated teeth. It allowed our imagination to wonder how his music had sounded before dire circumstances silenced it. There was the key. Past personal calamities were important factors, that fueled our need to romanticize and made any comeback all the more stirring. Promotion people took full advantage of that human trait and, although we were smart enough to know what they were doing, we fell in line and did as hyped.

It was amazing, when you think about it. Young people in a Nordic land embracing and fantasizing over a culture that couldn't be more different from their own, and it came complete with a musical score. We loved these sensuous, rhythmic sounds that made our bodies move like no Danish music ever had, and our new pied pipers conjured up all kinds of fantasies. We found magic in such names as Kid Ory, King Oliver, Johnny Dodds, Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey. Some of us became as familiar with the street names of New Orleans as we were with our own. We wanted to be there, to stroll through Congo Square, breathe in the air of what had once been the Storyville district, or just walk down Toulouse Street and make a right on Dauphine.

Some wanted to take the new obsession beyond fantasy. No, there weren't any attempts to start rice fields, nor did ornate iron balconies alter the look of our neighborhoods, but there were upstart local bands that tried to capture the right sounds, fluffs and all. The relatively sedate Trumbauer-inspired Swing Sweet and Hot Club Band had satisfied a certain need, but it lacked the nitty gritty of newer groups, like the Ramblers and the Bohana Jazz Band, two foot-stomping groups that gave us reasonable simulations of New Orleans music, sans the surface noise.

|

| Karl in my cluttered computorium on one of his visits to NYC. |

And then there was Karl Emil Knudsen, a young employee of the Copenhagen telephone company (KTAS), who perhaps was more smitten than the rest of us, but somehow managed to maintain his composure as he made tangible his own fantasies. His first step was to start a record label. Storyville Records made its inauspicious start with three or four re-re-reissues. We are talking 78s here, and, physically, these were about as thick they come, and the sound as bad as it gets, but if you listened carefully, there was Ma Rainey, her voice barely penetrating the surface noise, and James P. Johnson on a roll, a piano roll that someone had pumped at the wrong speed, and there, too, were Louis and Sidney Bechet with Clarence Williams, drowning out the voice of Alberta Hunter as they all played their derrieres off in glorious sub-fi.

When I said that these were re-re-reissues, I meant it. Karl had simply lifted them from Riverside Records, a new American label that had achieved the seemingly impossible: making the sound quality of Paramount and Gennett 78s twice as muddy as anything we had heard before. It didn't matter to us, not back in those early postwar years. We loved what was coming out of those grooves, even though we only heard the half of it.

Karl's next step was to find a place where we all could let our hair down and defy our genes with slightly artificial body motion. Take a look at any early, all-white American Bandstand kinescope and you will see what I mean—some of us just ain't got rhythm. Karl found the perfect spot on Hambroesgade, a dinky Copenhagen street in a dock area. The one-story structure looked like it might have been a place where dockworkers assembled. With its well-worn wood floors, drab cement walls and general lack of color, the place was about as uplifting as a Bozie Sturdivant lament, but, like Bozie's singing, it also had an unmistakable inner beauty. I mean, we wouldn't have wanted it to look like the Copa, or even the Cotton Club—the place was almost tailor-made and Karl made it come alive on Saturday nights.

|

Diplom's 1953 Winter catalog. The cover was designed by yours truly, GA, the "G" standing for my middle name, Gunnar. |

There were no roving searchlights, furs or shiny limos on the November night in 1952, when it all started. Word had quickly spread about this new club, a place where one could actually dance to live New Orleans music, dress casually, and spend no more than a tram fare. Tax laws required 24-hour advance membership enrollment, which took place at record shops, like Diplom Radio, a favorite hangout where Bent Haandstad guzzled beer, burped, and passionately recommended records. It cost but a pittance to become a member, and the price of admission to the club was equally affordable.

To give you an idea of the interest in Karl's Storyville Club, I signed up immediately and became member number 299. On opening night, I pointed my bicycle in the direction of Hambroegade, where I added it to a fast-growing tangle of wheels and handlebars. We never talked about it, but I think Karl and his fellow entrepreneurs must have been overwhelmed by the initial turnout—I know that I was. Although I had been consumed by a love for jazz for almost five years, I did not know anyone who shared my interest, and I was too shy to strike up a conversation when I attended lectures on the subject. In fact, I always found a seat way in the back. It's hell to harbor a burning interest in something and not be able to share it with anyone, so I found this new club to be more than just a place to spend Saturday nights, it was a wonderful remedy for my loneliness. Oh, I had friends from art school and work, but they saw my passion for jazz as a passing fancy that surely would dissipate with maturity. My mother thought so, too—when she felt a need to explain why I seemed glued to my HMV gramophone, she assured visitors that it was something I would soon get over. Of course, the real reason for my physical attachment to the old machine was that the spring had broken and I could not afford to have a new one made (the world had moved on to electrically powered turntables). There is an old Danish saying that "the naked woman soon learns how to weave" (i.e.

necessity is the mother of invention) and it didn't take me long to realize that I could play my records at the correct speed, 78 rpm, by placing my index finger on the label and pushing as hard as I could, making a circular motion. Of course, this meant that I could not walk away from the machine without the music stopping, but there was also an advantage to my unpatented, manual method: I was forced to give every note of the music my undivided attention. Soon, all my record labels were worn, some to a point where the information could no longer be seen, but I recognized matrix numbers and the visual character that audio frequency lends to a disc. For example, the surge of brass that follows Francis Wayne's vocal on Woody Herman's "Happiness is Just a Thing Called Joe" tried the limits of the groove's ridges and made that particular side readily identifiable. Yes, it's silly, and so is the fact that I had a callus in the middle of my index finger from passing over the spindle 78 times per minute.

|

| A re-enactment sixty years later. |

Getting back to Hambroesgade and the jazz hub that Karl spearheaded into existence. It wasn't the Mocambo, Stork or Cotton Club, but the glitter was there. No, a photo would not have captured it, for it was in our eyes and minds: a glow of anticipation and excitement that lit up this dreary dockside place on opening night. If there were stars, they were the members of Copenhagen's inner circle of jazz, men (pictured below) whose love for the music drove them to plan great things for the rest of us. Others—not pictured here, but certainly at the forefront of things—were Torben Ulrich, a tennis star who handled a clarinet with as much ease as he did a racket, Arnvid Meyer, his trumpeter and a future jazz archivist of great importance to jazz in Denmark, and Børge Roger-Henrichsen, a fine pianist who headed the Danish Radio's jazz department. There were others, like Anders Dyrup, and the circle was ever growing—the spark that seven years later would ignite the almost legendary Jazzhus Montmartre had been lit.

Of course, the Montmartre became known throughout the world, it was a place that began with New Orleans clarinetist George Lewis on the bandstand but soon became a venue that booked top contemporary players, like Dexter Gordon and Stan Getz. As we stood in line and slowly moved toward the entrance to Karl's club, we couldn't have imagined players of such stature paying Copenhagen more than a quick concert visit. But we weren't even thinking of such things, our minds were on this new adventure. The entrance, as I recall it, was a nondescript wood door, probably one step up from the street. It led to an outer room with a table on which sat a membership roster and a small cash box. A couple of people checked names and sold admission while Karl paced nervously and supervised the mounting of a crude sign over the door. It identified the room beyond as the "Storyville Club." If I remember correctly, there was also a hastily drawn sign with a magic two-letter word: "

ØL" That means beer, which was about all any of us could afford, but it was also a drink of choice. Here it was sold by the bottle, straight out of the wooden box.

The room itself was fairly large, with tables and chairs scattered about and a raised platform with an upright piano. So far, it was all anticipation, but that was thick enough to cut with a knife. Then something began to happen, guys were turning the raised platform into a bandstand. A month earlier, Karl had quietly entered the record business by recording trombonist Chris Barber with a young Danish group, The Ramblers. The four selections were released on a new label, Memory Jazz, around the time of the club opening. The band's leader was trumpeter Jeppe Esper Larsen, who quickly became the hottest local musician round, and now he was mounting that raised platform, instrument case in hand. Chris Barber was there, too, so you can imagine the excitement. I think I saw Karl smile, but I can't be sure.

Soon we all felt that we were, indeed, down by the riverside. At the time, I was working as an apprentice in the art department of Fona, a chain of music stores that covered the country and had several branches in Copenhagen. There were thus many display windows to be made attractive, and we did the artwork, which rotated among the branches, excluding the two huge windows of the main store, which were given special consideration.

One of our assistant branch managers was a guy named Eyvind Lindbo, nicknamed "Fesser". I had seen him a few times, when he came through the art department, but we never spoke, Imagine my surprise when I saw him at the Storyville Club opening, not just as a member, but as one of the "in" people. It took me a while, but I finally got up enough courage to approach him at the club and suggest that a more professional sign would look better over the entrance. He suggested that I make one.

The following Saturday, having spent a good part of the week working on it, I brought the club a new sign. Now the smile on Karl's face was unmistakable and he liked it so much that he asked if I might be able to come up with something to liven up the drab walls. This proved to be my ticket to the inner sanctum.

|

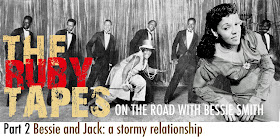

| The inner circle. On the far left is Boris Rabinowitsch, he was our first post war "modern" pianist, today he writes about the music. Behind him stands Jeppe, whose band performed with Chris Barber at Storyville's opening. That's Karl Emil Knudsen in the center and Bent Haandstad standing behind him, holding his magazine, Jazz Parade. The man seated on the left is J. A. Lakjer, he owned a jazz record shop and published a magazine called Jazz Revy. This was a December, 1952 summit meeting and I was still very much an unknown outsider. |

Next week I will conclude this recollection of Karl and reminisce about the time when he brought to Denmark the Ken Colyer Jazz Men band, which I recorded for Storyville's first original release. I will also recall the "Riverboat Shuffle" that Karl created on Øresund, the sound that separates Denmark and Sweden at their closest point (there is now a bridge).

Here is the first recording I made of the Colyer band, April 11, 1953, when it made a one-time appearance at Lorry's 7-9-13 Club, part of a Copenhagen entertainment complex that featured Alberta Hunter and other notables in the 1930s. This tape was not meant for release, I was really just testing the equipment (a B&O home recorder and a single ribbon microphone), but Karl and I found it worthy of distribution.

Enjoy "Tiger Rag":

|

| L to R: Monty Sunshine, Lonnie Donegan, Ken Colyer, Ron Bowden, Chris Barber, Jim Bray |

.jpg)