At this point, Barney Josephson joined Alberta in the booth. She had become very fond of Barney, but her admiration would diminish somewhat when she learned that he had stood in the way of her getting some lucrative outside jobs. If you listened to the first audio clip, you probably gathered that Alberta was not very fond of the IRS. She had worked more than a lifetime, made very good money, and paid a lot of taxes—more than enough. The time had come, she believed, where she had paid in full, so it angered her that the IRS now was pursuing her for more. That's why she instituted a new policy: cash only. She was charging and receiving $10,000 for each performance outside of The Cookery, and it was not because she needed the money—for more years than many of us experience on this earth, Alberta had been making money and spending it prudently. My first inkling of her being well above the poverty line came when she called to say that she would be a half hour late for a Library of Congress interview I was conducting. "You know those ten thousand dollar bonds that are supposed to be so terrific?," she asked me. I had to confess that those bargains had somehow escaped me. "Well, they're really supposed to be very good, so I'm going to stop at the bank a pick up a couple."

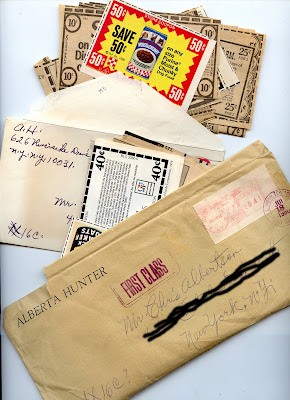

Having lived through the Great Depression and seen people lose their money as banks closed, she wasn't taking any chances. She kept money in at least four different banks, and had enough tucked under her mattress to keep the Weather Girls eating for a few years. I became aware of her lay-away plan one day when she insisted that I take a cab home from her Roosevelt Island apartment, because I didn't have my usual ride—Alberta was frugal, not cheap. As was her habit, she had laden me down with groceries. Like I said, Alberta could not resist a supermarket bargain, whether she needed the food, or not, and the latter was usually the case, because she ate like a sparrow. Consequently, her three apartments were as well stocked as some neighborhood bodegas. "Let me give you some money for the cab," she said as she walked over to her bed and lifted the mattress.

Having lived through the Great Depression and seen people lose their money as banks closed, she wasn't taking any chances. She kept money in at least four different banks, and had enough tucked under her mattress to keep the Weather Girls eating for a few years. I became aware of her lay-away plan one day when she insisted that I take a cab home from her Roosevelt Island apartment, because I didn't have my usual ride—Alberta was frugal, not cheap. As was her habit, she had laden me down with groceries. Like I said, Alberta could not resist a supermarket bargain, whether she needed the food, or not, and the latter was usually the case, because she ate like a sparrow. Consequently, her three apartments were as well stocked as some neighborhood bodegas. "Let me give you some money for the cab," she said as she walked over to her bed and lifted the mattress.

|

At least once a month, the mailman brought me an envelope stuffed with dog food coupons for my dobermans, Mingus and Bessie. |

I am not exaggerating when I say that I had never before—or since, for that matter—seen so much cash in real life. Remember the H.C. Andersen tale of the princess who spent a sleepless night because a pea was placed under her mattress? Well, this reminded me of that and I don't know how Alberta ever got a good night's rest. Recently, when I learned that my friend, Jean Claude Baker, had also seen Alberta's mattress bank, I asked him how much he thought she had under there—I had estimated 60 or 70 thousand dollars, he put it at twice that amount.

On the tape that accompanies this post, you will hear Barney say that Alberta "asked me to look after her affairs," but that was actually not so. The idea of becoming her manager was his, borne out of greed, one might say. She once told me how wonderful Barney was not to charge her for his managerial services, but there was method to his madness. As her extraordinary comeback received more publicity, the demand grew for her to perform at private and company functions. Each time she appeared somewhere else, Barney faced a near-empty room, and lost money, but, as her manager, he would have some control over that. Remember, Alberta was earning much more on these side bookings than she could make at Barney's place, so she wasn't going to turn them down—at least not the lucrative ones. That, however, is exactly what Barney began to do, and Alberta knew nothing of it until I told her.

Barney liked to inflate his own role in the comeback of Alberta Hunter. The truth is that Charlie Bourgeois, the Newport Jazz Festival's PR man and George Wein's trusty right hand, crossed paths with Alberta at one of Bobby Short's parties and was taken by her youthful demeanor. It was her first social outing in many years and she looked radiant as she, Bricktop and Mabel Mercer shared precious recollections of a distant past. "You know something, honey," said Bricktop, "you should go back on the road!" That was Charlie Bourgeois' cue. "You ought to give Barney Josephson a call," he suggested, "I bet he would love to book you."Bricktop and Mercer agreed.

"If that's so," Alberta replied, "let him call me."

|

| Ram Ramirez, Jimmy Rowles and Claude Hopkins were contenders. |

You will hear Barney's version of how Gerald Cook came into the picture, but that is pure fabrication. It was Harry Watkins who brought him in—ironically, as you will see.

I had an old upright at that time, so I suggested that she audition pianists at my apartment. Ram Ramirez (co-writer of Lover Man with Jimmy Davis) was the first contender, but he was having some trouble getting with her repertoire and that did not bode well, thought Alberta. Then I suggested former band leader Claude Hopkins, who had been around longer and had proven quite adaptable when I had him play for Lonnie Johnson on a Prestige session. Alberta liked his work, but with some reservation. She also feared that his name might be too well known and thus could overshadow hers. Someone, I think it may have been Charlie Bourgeoise, recommended Jimmy Rowles and Alberta immediately liked the fact that he had accompanied Billie Holiday, so—when their personalities clicked—she gave her approval and that's who she made her Cookery debut with on October 10, 1977. A bunch of us were there and Alberta's performance—musical and otherwise—belied the many years that had passed since she retired from show business.

Alberta eventually concluded that Jimmy Rowles was "too modern," so her old friend, Harry Watkins, came up with Gerald Cook. He had never heard of Alberta and didn't seem to eager until he found out that she was a lady with a long and very impressive career behind her. Then he took the job and, sad to say, his playing was just what she wanted. What made it unfortunate is that Gerald Cook turned out to be a crook. We din't find that out until Alberta died.

Harry Watkins called and asked me if I had heard of Alberta's death. I hadn't, and he had just learned of of through a friend who happened upon a notice in the papers. It turned out that Gerald Cook, who had a key to Alberta's Roosevelt Island apartment, found her dead, seated in her favorite easy chair—he had gone over there at the urging of Harry, who felt that there was something wrong when Alberta didn't answer her phone. That made Harry wonder all the more why Gerald had not called him back with the news, knowing full well how close they had been since the Dreamland days. Several days later, Gerald finally gave Harry a call with the sad news. That same day, he called me and asked if I would speak at a memorial service to be held at Pastor Gensel's St. Peter's Church. At first, I declined, but changed my mind after some thought, telling him to schedule me as the last speaker. I wanted to base my words, to some extent, on the BS that would inevitably precede them.

I was not really surprised to hear of Alberta's death. She had been feeble for awhile—her memory was no longer as sharp as it had been, she repeated herself and sometimes seemed to drift off. The very quick-minded, never-felt-better Alberta I had known for over twenty years was gone. She would return to something resembling her old self, but only briefly and sporadically, and with increasing infrequency. I first sensed that change on a visit to her apartment, about a year before she started to fade. This lady, who adamantly refused to acknowledge the possibility of her death, asked me to sit down with her at her living room table to discuss "something very important." It turned out to be her will. "I don't need to know about your will," I told her, feeling rather uncomfortable. "Yes you do," she said, placing the papers in front of me.

She told me that she had accounts in four different banks and that she had four people in her will, each of whom would inherit the content of one bank. Her four heirs were Harry Watkins, Sam Sharpe, Jr.—her only known relative, who lived in Denver—her old friend, singer Jimmy Daniels, and I. Now I was really embarrassed, but appreciative and surprised. Alberta went on to say that her music copyrights would also go to me, because only I knew how to handle renewals. Then she showed me the will and asked me to take a good look at it, which I did. I was still stunned by the mere fact that she had brought up the subject of death.

A few months later, in June of 1984, Alberta was deeply affected by the death of Jimmy Daniels, especially since an earlier and minor falling out was left unresolved. It had been a year of old friends slipping away, including Mabel Mercer and Bricktop. Alberta felt that she would probably be "the next to go," and the rewritten scenario clearly angered her—she became cranky and annoyed with Barney and Gerald Cook, refusing to speak to either of them. Harry and I were somehow spared, probably because neither of us were involved in her working life. I know it's pure conjecture on my part, but I think she was upset because she finally saw the end of the tunnel. It had been such a great and rewarding life—how dare God stop the show! God? Alberta always said that she wasn't religious and she did not attend church, but she wasn't fooling anyone—the faith was there, but sans hypocrisy.

Just as I had predicted, the memorial service was a study in hypocrisy. Jon Hendricks spoke warmly and sincerely, admitting that he was more an admirer than a friend, Rosetta Le Noir laid it on a bit thick, stretching a fairly casual association into a lifelong friendship, John Hammond was characteristically deceptive as he gave the impression of having known Alberta for many years, and Barney? Well, good old Barney was a chip off the old Hammond block. He wanted to be remembered for having brought Alberta back.

When my turn finally came, I set the record straight. Addressing John Hammond, I reminded him of the fact that, "It was not so long ago that I introduced you to Alberta—you didn't seem too interested, but look what happened." The attendees sent a ripple of titter down the aisles as I turned my attention to Barney. "Alberta," I said "turned The Cookery into a shrine for herself and a gold mine for you." More titter, less subtle. I ended my little speech by pointing upwards. "I have a strong feeling that Alberta has been taking all this in from up there, and that she has separated the wheat from the tare."

When I walked away from the microphone, Pastor Gensel approached me. "Wonderful, Chris," he said, placing his arm on my shoulder, "it needed to be said."

Neither John nor Barney spoke to me again.

A few days after the memorial service, I received a call from Harry Watkins. He was shaken and almost in tears. He had just received a call from Gerald Cook asking if Alberta had left her iconic gold earrings in the Riverside Drive apartment they had shared. When Harry told him that the earrings were, indeed, there, Gerald raised his voice and said that they had better be there when he arrives to pick them up. "I don't know if Gerald has been drinking," said Harry, but I am scared. I told him to lock the door and be ready to call the police if Gerald showed up. Then I started putting together the pieces of what was becoming a puzzle. Why had Gerald waited several days before informing us of Alberta's death? Had he helped himself to the greenery under her mattress? What became of the will? I called Harry back and he was still upset, but Gerald had not shown up. Had Alberta told him of her will? No, but she had mentioned that he would not have to worry about losing the apartment.

I decided to track down Alberta's will and I finally received a copy from the court. This was not the will she had shown me. This one left everything to Gerald Cook! Well, except the jewelry—which in itself amounted to a small fortune—that was all bequeathed to Gerald's sister in Chicago, someone Alberta barely knew! It would not have taken Sherlock Holmes to detect that something didn't add up. The changes were initialed by Alberta—or were they? The fact is that she had been so weak and feeble-minded towards the end that she probably did not know what she was doing. Had she even read the changes? Writing me out of the will would not have been particularly odd, but Harry? Her nephew Samuel? Even if Alberta's relationship with Gerald had not deteriorated, this would not have made any sense. And why did the attorney—a man who specialized in copyrights and had been recommended to Alberta by John Hammond—not find this change to be beyond credulity? He knew that Alberta was no longer of sound mind, but he went along with this.

I shared my discovery only with a couple of friends, including Gary King, who was with me when Alberta showed me her will. It is only because I was in the original will that I did not make an issue of this—people would think that I was looking out for my own interests. Now, decades later, I am not so sure that I should not have spoken up for Harry and, in a sense, for Alberta. Gerald Cook moved to Europe where, I am told, he drank himself to death.

Here, Barney Josephson embroiders the story of his association with Alberta, and she—being a thorough PR pro—goes right along with it. That's showbiz!

I should, however, make it clear that Barney had many real accomplishments that he could be proud of and, rather than list them here, let me give you a link to Wikipedia's entry for the Café Society clubs.

Let me also recommend "Cookin' at the Cookery." a play by Marion J. Caffey that has been seen in regional productions throughout the U.S. in recent years. It is a very accurate depiction of Alberta's final climb to higher ground. I also recommend Frank C. Taylor's biography, "Alberta Hunter: A Celebration in Blues." Alberta met Frank when she performed in Rio and she was very fond of him. Unfortunately, she passed before the book was published, otherwise Gerald Cook would not have been able to wangle a co-author's credit (and, I presume, a cut of the royalties). He was a good pianist, but shed no tears for him.

Harry Watkins called and asked me if I had heard of Alberta's death. I hadn't, and he had just learned of of through a friend who happened upon a notice in the papers. It turned out that Gerald Cook, who had a key to Alberta's Roosevelt Island apartment, found her dead, seated in her favorite easy chair—he had gone over there at the urging of Harry, who felt that there was something wrong when Alberta didn't answer her phone. That made Harry wonder all the more why Gerald had not called him back with the news, knowing full well how close they had been since the Dreamland days. Several days later, Gerald finally gave Harry a call with the sad news. That same day, he called me and asked if I would speak at a memorial service to be held at Pastor Gensel's St. Peter's Church. At first, I declined, but changed my mind after some thought, telling him to schedule me as the last speaker. I wanted to base my words, to some extent, on the BS that would inevitably precede them.

I was not really surprised to hear of Alberta's death. She had been feeble for awhile—her memory was no longer as sharp as it had been, she repeated herself and sometimes seemed to drift off. The very quick-minded, never-felt-better Alberta I had known for over twenty years was gone. She would return to something resembling her old self, but only briefly and sporadically, and with increasing infrequency. I first sensed that change on a visit to her apartment, about a year before she started to fade. This lady, who adamantly refused to acknowledge the possibility of her death, asked me to sit down with her at her living room table to discuss "something very important." It turned out to be her will. "I don't need to know about your will," I told her, feeling rather uncomfortable. "Yes you do," she said, placing the papers in front of me.

|

| Alberta had her own radio show in the late 1930s. |

A few months later, in June of 1984, Alberta was deeply affected by the death of Jimmy Daniels, especially since an earlier and minor falling out was left unresolved. It had been a year of old friends slipping away, including Mabel Mercer and Bricktop. Alberta felt that she would probably be "the next to go," and the rewritten scenario clearly angered her—she became cranky and annoyed with Barney and Gerald Cook, refusing to speak to either of them. Harry and I were somehow spared, probably because neither of us were involved in her working life. I know it's pure conjecture on my part, but I think she was upset because she finally saw the end of the tunnel. It had been such a great and rewarding life—how dare God stop the show! God? Alberta always said that she wasn't religious and she did not attend church, but she wasn't fooling anyone—the faith was there, but sans hypocrisy.

|

| Alberta and friends at Bricktop's popular gathering place in Paris. |

When my turn finally came, I set the record straight. Addressing John Hammond, I reminded him of the fact that, "It was not so long ago that I introduced you to Alberta—you didn't seem too interested, but look what happened." The attendees sent a ripple of titter down the aisles as I turned my attention to Barney. "Alberta," I said "turned The Cookery into a shrine for herself and a gold mine for you." More titter, less subtle. I ended my little speech by pointing upwards. "I have a strong feeling that Alberta has been taking all this in from up there, and that she has separated the wheat from the tare."

When I walked away from the microphone, Pastor Gensel approached me. "Wonderful, Chris," he said, placing his arm on my shoulder, "it needed to be said."

Neither John nor Barney spoke to me again.

|

| Performing at The Cookery. |

|

| Harry Watkins and Alberta at her Roosevelt Island apartment. Two months later, she was gone. |

I shared my discovery only with a couple of friends, including Gary King, who was with me when Alberta showed me her will. It is only because I was in the original will that I did not make an issue of this—people would think that I was looking out for my own interests. Now, decades later, I am not so sure that I should not have spoken up for Harry and, in a sense, for Alberta. Gerald Cook moved to Europe where, I am told, he drank himself to death.

Here, Barney Josephson embroiders the story of his association with Alberta, and she—being a thorough PR pro—goes right along with it. That's showbiz!

I should, however, make it clear that Barney had many real accomplishments that he could be proud of and, rather than list them here, let me give you a link to Wikipedia's entry for the Café Society clubs.

Let me also recommend "Cookin' at the Cookery." a play by Marion J. Caffey that has been seen in regional productions throughout the U.S. in recent years. It is a very accurate depiction of Alberta's final climb to higher ground. I also recommend Frank C. Taylor's biography, "Alberta Hunter: A Celebration in Blues." Alberta met Frank when she performed in Rio and she was very fond of him. Unfortunately, she passed before the book was published, otherwise Gerald Cook would not have been able to wangle a co-author's credit (and, I presume, a cut of the royalties). He was a good pianist, but shed no tears for him.