We landed in New York and went straight to the Capital Hotel which was recommended by one of our American friends at Keflavík. A nice, reasonably priced hotel, it was located on Eighth Avenue at 49th Street, almost across the street from Madison Square Garden, an unimposing, grimy building in whose arena historic events had taken place since 1925. It should have been declared a landmark, but it became a parking lot in 1968.

I don't recall what the room rate was at the Capital, not much by today's standards, still—having spent our first night there, Hanne and I decided that we should find a cheaper place and spend more money on Christmas gifts. The place we found was right around the corner, the "Newly Renovated Madison Square Hotel." Well, it turned out that the only thing they had newly renovated was the front door, but that was okay—a small room for a small price.

I don't recall what the room rate was at the Capital, not much by today's standards, still—having spent our first night there, Hanne and I decided that we should find a cheaper place and spend more money on Christmas gifts. The place we found was right around the corner, the "Newly Renovated Madison Square Hotel." Well, it turned out that the only thing they had newly renovated was the front door, but that was okay—a small room for a small price.There was no TV, but it had a radio that worked when you fed it quarters. Hanne discovered that it also liked Icelandic five aura pieces, which were worth less than a cent, so it practically stayed on all the time and there was good jazz coming out of it.

The hotel was an old brick building back then, and far more pleasing to the eye than it became when the renovation went beyond the front door. Now it has an odd faux 3d bathroom tile look (see photo).

Some of our American friends at Keflavík had asked us to look up their parents, which led to two dinner invitations in Brooklyn and broadened our knowledge of cultures. We were, for example, introduced to Jewish food by Mrs. Lefkowitz, whose son, Marvin, was in the Army and lived off base with his wife, Marsha. They had become our good friends and they happened to live next to our fabulous home (pictured on the left). When the food lacked salt, Hanne and I wrongly concluded that salt was something Jewish people did not use. It would not have surprised us if Marvin's mother had served pork chops, because we were quite ignorant when it came to other ethnicities. In Denmark—back then, at least—it was not important to know another person's religion. Victor Borge performed under his birth name, Børge Rosenbaum, because that is how he had established himself before the war. It was only when he came to the U.S. that he needed to adapt the veil of a pseudonym. When I later started working at WHAT-FM in Philadelphia, I discovered that all my fellow disc jockeys on the stations white (i.e. FM) side were working under assumed names that made their Jewish origin less apparent. I found it quite amazing that there was a need for that. I think Marvin and Marsha probably mentioned to us that they were Jewish, but they did not make us aware of ethnic differences—I'm sure we served them eggs and bacon. Of course, I knew that Jewish people existed and I was fully aware of the collective effort by non-Jewish Danish citizens that in 1943 resulted in rescuing over seven thousand Danish Jews from being sent to Nazi camps. I just didn't know why there was this ethnic division. As far as I know, there were no Jewish areas of town and I never picked up a disparaging word. Perhaps I was just super uninformed and naïve. It was when I came to live in the U.S. that my eyes really opened to the fact that American ethnic discrimination was not just aimed at black people. As for Jewish food. I was already familiar with much of it—I grew up with much of it, but we called it German food and it was often prepared by people with German names. Life is a constant learning experience and some of us are just slower than others.

Our other dinner invitation was to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Melady, a middle-aged couple whose son, Jack, was a trombone player in the Air Force band. Jack had also become a good friend and I admired his eclectic musical taste and, of course, shared his more than casual love for jazz. He also played the harp—the Lyon and Healy kind—and was very good at it. Jack liked to play jazz on his harp and he knew that he would face less competition if he focused on that rather than the trombone, so, upon his release from the Service, he used the GI Bill to study harp at the Royal Conservatory in Copenhagen. When we renewed contact, in the Sixties, he had his own album out on the Sue label, had appeared on a 1965 Lucky Thompson Prestige date, and worked intermittently with the Clancy Brothers. I don't know what became of Jack, but I still recall vividly the evening Hanne and I spent at his parents' house on the last evening of our trip. They were Irish-Catholic and Mrs. Melady was a very devoted one, as we discovered when, after a wonderful home-cooked meal, she poured coffee and, with dramatic flourish, produced a small brown bottle of holy water. "This," she said dropping a dash into our cups, "will give you a safe journey home." Then, as we enjoyed an after dinner drink in the living room, she brought out a small wood carving of a saint, held it up for all to see, and handed it to Hanne. "That's very beautiful," Hanne remarked, giving the little statue a turn. "I know," said Jack's mother, "and tomorrow I am going to have it blessed."

"Oh," exclaimed Hanne, "I think it looks wonderful the way it is, I wouldn't have anything done to it."

Before we left Iceland, Mr. Roger, the chief OSI agent (that's Office of Special Investigations) told me that his cousin was the head of NBC's scenic department and suggested that I look him up. I did, and he turned out to be a delightful man who greatly appreciated receiving a personal message from his far away cousin. He apologized for not being able to see us or take us to dinner, but they were deeply immersed in a rather elaborate set design, so he couldn't get away. "But would you like a tour of the NBC TV studios?," he asked. Of course we would and that proved to be far more interesting than we anticipated. No ordinary tourist tour, but a behind-the-scenes experience that almost made us feel like VIPs. We were introduced to many of the network's biggest personalities and visiting stars, but the high point for me came when Steve Allen gave us tickets to the Tonight Show, which he hosted. The Benny Goodman Story was to open after the New Year and Steve (then still Mr. Allen to me) was devoting the entire show to the man he had portrayed. Benny himself would be there with some of his star sidemen and it promised to be an evening of great music. As I recall, it was. I suppose there exists some footage of it, at least a blurry kinescope, but I haven't seen or heard of any. (See update at bottom)

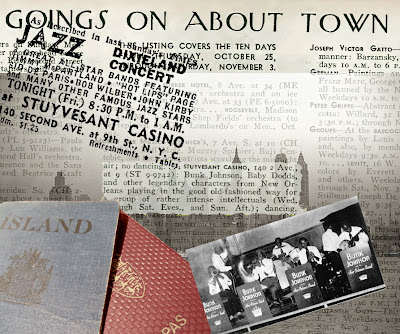

So, contacting Mr. Rogers' cousin turned out well. More about that in a later segment of this story. I also had another number to dial, SUsquehanna 7-5690. I was about to hang up when, after about five rings, I heard phone fumbling followed by a slow, slurred "hello." It was Timme Rosenkrantz, the Danish jazz baron whom I had met in Copenhagen a couple of years earlier. He was the one who took me to Lionel Hampton's 17th wedding anniversary party in Copenhagen and helped me get Hamp and the band to an all-night Storyville Club jam session. See The Night I Taped Brownie). Timme and I would share an apartment five years later, but I really didn't know him all that well at this point. When I mentioned that Hanne and I wanted to hit some jazz spots, he perked up and told me to meet him at Stuyvesant Casino, on Second Avenue and 9th Street. "And bring plenty of money," he added.

When we walked into the Stuyvesant's corridor-like front room, the sound of Coleman Hawkins greeted us from a room beyond. A hat check lady with flirty eyes and a Pepsodent smile asked us each for a quarter and pointed us in the direction of the music. At the entrance to the room, an elderly man relieved us of a couple of bucks, the price of admission, then he handed us over to a smiley waiter who seated us and took our order. Timme was nowhere to be seen, but the mention of his name brought a glimpse of recognition to the waiter's eyes "He'll be here," he said with assurance. I ordered a large pitcher of beer for a dollar and wondered what Timme had meant when he told me to bring plenty of money. Probably a joke, humor was a big part of Timme's personality.

|

| A click on this will enlarge it |

Stuyvesant Casino was where Bunk Johnson, Jim Robinson and George Lewis had introduced New Yorkers to New Orleans jazz nine years earlier. The big city crowd was fed all those stories about Bunk's new teeth and how he was a rice field discovery; they also loved to hear that George Lewis was a dock worker and that the music they played was the essence of jazz in a state of resurrection. It was wonderfully primitive, they had been told. There was nothing primitive about the band we were hearing. It may not have been as glorious as I would like to recall, yet—given the cast—it probably was. A Coleman Hawkins band du jour, with Sonny Greer in full command of a percussion setup that looked like his old Ellington drum kit in the buff. Max Kaminsky, Vic Dickenson, and Cecil Scott were there, too, and the pianist was Frank Signorelli, a historic veteran of the Original Dixieland Jass Band. After about an hour, there still was no sign of Timme. Hawkins and company had left the stage to make room for a dixieland group, the Red Onion Jazz Band. They were gearing up when Hawkins passed by our table and was stopped by our helpful waiter, who asked him if he had seen the Danish Baron. Hawkins said Timme might be across the street, at the Central Plaza. We decided to take a look.

The Central Plaza's main course was a no holds barred jam session. The room was larger, the crowd was louder and rowdier, the music faster and earthier. As we entered, Buck Clayton had them dancing between the tables, fueled by the music and, again, one dollar pitchers of beer, but here there were also bottles of the hard stuff all over the place and as I scanned the room for a sign of Timme, I counted eighteen watchful cops—this joint was jumpin'. We hadn't seen or heard anything, yet. Suddenly, a young trombone player made an agile move to the top of the piano and the rhythmic frenzy boiled over—it was as if someone had hit a fast-forward button. The trombonist was a not-yet-thirty Conrad Janis. Already an accomplished actor, he will forever be remembered as Mindy's father in the Mork and Mindy sitcom. His mother, Harriet Janis co-wrote, with Rudi Blesh, the definitive book on ragtime, They All Played Ragtime, and he was probably the busiest musician in all of New York. He had his own band at The Central Plaza and he was a regular at other spots, including the Metropole Café, our next stop. As you can see here, I got to know the Metropole better in 1957, when I returned on an immigration visa, exchanged my cursed blue button of Keflavík for a green card of hope, and had my initial encounter with roaches! It was a learning experience that I would not wish to repeat.

Hanne and I had just purchased a shrunken head for Bengt, her brother-in-law and some truly cheap looking, esthetically offensive initialed hand towels for another relative who would find them beautiful, never use them for anything but display, and thus preserve the adornment of glittery initials and poodles. Sure, we had bought them with a twinge of guilt, but a gift for another relative was even uglier and just as useless. It looked like a half lampshade and it was supposed to go on the foyer wall where it could hold gloves. Even thinking about these things over half a century later gives me chills. You might wonder why we didn't get them something really nice—I think it's because we were catering to their poor taste, and the fact that they probably expected something a la canine pool players on black velvet. At that time, the mention of America conjured up in European minds gaudy things made of plastic. Now, the head was another matter, it was something we felt certain Bengt, an artist, would love. We will never really know, but I'm getting ahead of myself.

Hanne and I had just purchased a shrunken head for Bengt, her brother-in-law and some truly cheap looking, esthetically offensive initialed hand towels for another relative who would find them beautiful, never use them for anything but display, and thus preserve the adornment of glittery initials and poodles. Sure, we had bought them with a twinge of guilt, but a gift for another relative was even uglier and just as useless. It looked like a half lampshade and it was supposed to go on the foyer wall where it could hold gloves. Even thinking about these things over half a century later gives me chills. You might wonder why we didn't get them something really nice—I think it's because we were catering to their poor taste, and the fact that they probably expected something a la canine pool players on black velvet. At that time, the mention of America conjured up in European minds gaudy things made of plastic. Now, the head was another matter, it was something we felt certain Bengt, an artist, would love. We will never really know, but I'm getting ahead of myself.Anyway, so there we were on our last day in New York, standing amid the Christmas bustle of Times Square, with the sound of Tennessee Ernie's Sixteen Tons clashing with that of bell-ringing Santas and Mr. Sandman. We were taking it all in when we heard a male voice behind ask what language we were speaking. "Danish," we replied, almost in unison. This seemed to please him, he whipped out a business card and asked if we would care to be contestants on a TV show. We were tempted when he added that we could win a large sum of money, but reason prevailed, it would be impossible to find another flight that would get us to Copenhagen by Christmas Eve. We thanked the man and crossed the street, each wondering whether we had just turned down a fortune.

As we exited for the last time through the newly renovated door of the Madison Square Hotel, with one head in a shopping bag and eyesores filling the others, Hanne and I began looking forward to having a traditional Danish Christmas with her parents. "I hope that holy water hasn't worn off," said Hanne, jokingly, as our cab slowly made it through midtown traffic and turned towards Idlewild.

The Icelandic airline was using Douglas DC 6 propeller machines that had been sawed in two and put back together with an extra piece of fuselage. The plane's body was thus quite long and one could see two seams that looked like a soldering job. As we approached the plane and began climbing the steps, which is what one had to do in those days, I pointed to the seams and said "Thank god for Mrs. Melady's holy water."

There was an early morning stopover in Reykjavík, a small airport situated as near to the center of town as any I have ever seen. You came in right over the rooftops. On this December day, the runway was icy and it looked like it had just stopped snowing. We felt an enormous jolt as the plane was about to touch down, stuff came flying from the overhead compartments and we felt the aircraft sliding at a slight angle, but it came to a stop and limped into its parking space. My mother had seen it all, the plane approached too low and its wheels struck a fence, dragging it along. But Mr. Melady's dash of holy water seemed to have worked, we were a bit shook up, but—compared to my mother—relatively calm. We had about an hour on the ground, so there was good time for a breakfast—things were lax in those days.

There was an early morning stopover in Reykjavík, a small airport situated as near to the center of town as any I have ever seen. You came in right over the rooftops. On this December day, the runway was icy and it looked like it had just stopped snowing. We felt an enormous jolt as the plane was about to touch down, stuff came flying from the overhead compartments and we felt the aircraft sliding at a slight angle, but it came to a stop and limped into its parking space. My mother had seen it all, the plane approached too low and its wheels struck a fence, dragging it along. But Mr. Melady's dash of holy water seemed to have worked, we were a bit shook up, but—compared to my mother—relatively calm. We had about an hour on the ground, so there was good time for a breakfast—things were lax in those days.An hour later, we were off again, but we probably should not have been—some things were too lax. We found that out when we reached the air space over Oslo, our next scheduled stop before Copenhagen. The pilot announced that we would not be able to land in the Norwegian capitol, because there was a "minor" problem with our wheels. It didn't seem so minor us when we heard that the wheels had been damaged by that Reykjavík bump and now refused to come down. We were told that there was nothing to worry about and that we would land as soon as we had used up the bulk of our fuel.

As the flight continued, the drinks became plentiful and on the house. People were now oddly quiet and the stewardesses were all but mum, except when they tried to get us to drink more. Finally, we were told that we would be landing on foam and that it was almost normal, because such landings were, somehow, commonplace. We were to remove all sharp objects from our pockets, place a pillow on our lap, and remain calm until the aircraft came to a stop and we received further instructions. Hanne was not in the mood for drinks, so I had more than my share, but nobody was panicking. Icelandic Airlines had an excellent safety record and its pilots performed a remarkable feat each time they had to hit the runway rather than a Reykjavík street. I, therefore, had full confidence in the pilot, but I did share Hanne's worry about family members possibly being at the airport and seeing us crash.

We needn't have worried, for this turned out to be a smoother landing than some of the regular wheels-in-place ones I had experienced. As for the family, nobody had informed us, but we weren't even near Copenhagen. Looking out the window, we saw a big red neon sign welcoming us to Hamburg.

"Ach," said the young man seated across the aisle from me, "das ist gut!." We had spent hours seated next to each other without exchanging a single word, but shared danger has a way of breaking a silence. By the time we and our fellow passengers had deplaned and were seated in one of the terminal's waiting rooms, Hanne, Carl Heinz and I had become old friends, exchanging stories of our respective trips to America. He, it turned out, was born in Chicago, which explained why he spoke English so well. He lived in Hannover, a city hit hard by Allied bombing (see photo) and was returning home from a visit with his parents. Had he spent the war in Germany? I asked. Yes, he had been sent to an engineering school in Berlin just before the war broke out, a school his father had graduated from before immigrating to America. Nice idea, but nobody could have known that the timing was the worst. Carl Heinz hadn't been at the school for long before war fever grabbed Berlin and he saw all his classmates signing up for military duty. The peer pressure was too strong to resist, so he followed suit. "What was a young man to do?," he said. What he did was join the submarine corps.

An airport rep approached us with a clipboard and pen poised for action. We were each asked to give him our seat number and a description of our carry-on luggage. "There's a paper bag," said Hanne, "with a head in it."

"A head?"

"Yes, a human head, very small," Hanne replied.

The man wrote something down and turned to Carl Heinz, who said he only had a small black leather valise, then continued his story.

"It was a terrible time," he said, "and I got caught up in it." When I asked him if he had served on a U-Boat, he nodded, "We spent much time off the coast of Baltimore, sinking Liberty ships and such. I am not proud of that, but war is a strange thing." I wondered if I should tell him about my two U-boat encounters, but decided against it—one of those U-boats might have been his, I thought. He went on to explain how he was captured and interned by the Americans at the end of the war, and how he one day had a surprise visit from an American army colonel who turned out to be his brother-in-law. That's how he gained an early release. Eager to visit his parents in Chicago, he applied for a visitor's visa, but was turned down for two reasons: volunteering for military service and having come within three miles of the U.S. coast during the war. It apparently did not make any difference that he was born in the States.

To get around those pesky rules, his father pulled a few strings and contacted his Congressman. Carl Heinz got his visa.

During the two or three hours we had to spend in the waiting room, our hand luggage was brought off the plane and returned to us. Soon, bottles of duty-free liquor were opened and a boring wait became a lively party. When we received our hand luggage and shopping bags, Hanne noticed that something was missing: we had lost our head! Was it a real one? I doubt it, but we'll never know, it probably rolled under a seat and scared the maintenance crew. Anyway, we never heard more about it.

When I told Carl Heinz that I would be traveling to Frankfurt in search of a job after the New Year, he insisted that I stop off in Hannover for a day and visit with him and his daughter. Hanne thought that was a good idea. We both almost felt sorry for the guy, the Nazi experience had obviously been a traumatic one and he seemed to be a very nice person. Perhaps, if I had spent the war years in Nazi occupied Denmark rather than in Forest Hills and Iceland, I might have been less willing to start a friendship, less naïve. As things went, my sympathy took a nose dive when I visited Carl Heinz a couple of weeks later. Yes, you guessed right: he was the Nazi on the plane. More about my awakening and adventures in Frankfurt, when this story continues.

6/8/10 Update: I made some additions and edits (my English is a work in progress). Also happy to report that the Goodman/Allen Tonight Show segment was, indeed, captured for posterity —thanks to my good friend John F. for that info.

Another great post, Chris. the post war years don't have nearly the coverage that the war years had, but they are full of great stories. thanks again!

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comment. I think the story gets better (as it grew worse, so to speak).

ReplyDeleteLove the peysuföt (did I spell it right?) photo on your blog. I have a photo of my Icelandic grandmother in one of those outfits.